While not many people would realise it today, most towns in this region, indeed across Victoria, had areas set aside known as Town Commons.

Words by Anthony Sawrey, with permission of The Local

Research by James Curzon-Siggers

It was just one instance of the widespread colonial practice in the 19th century of reserving specific pieces of land for a variety of public uses.

By 1890 more than 6,000 square kilometres existed as officially designated common land. Unfortunately much of this land has been divided up, built upon and sold off over the years and there are very few intact examples to be found anywhere in the state. However Clunes is one of those rare exceptions.

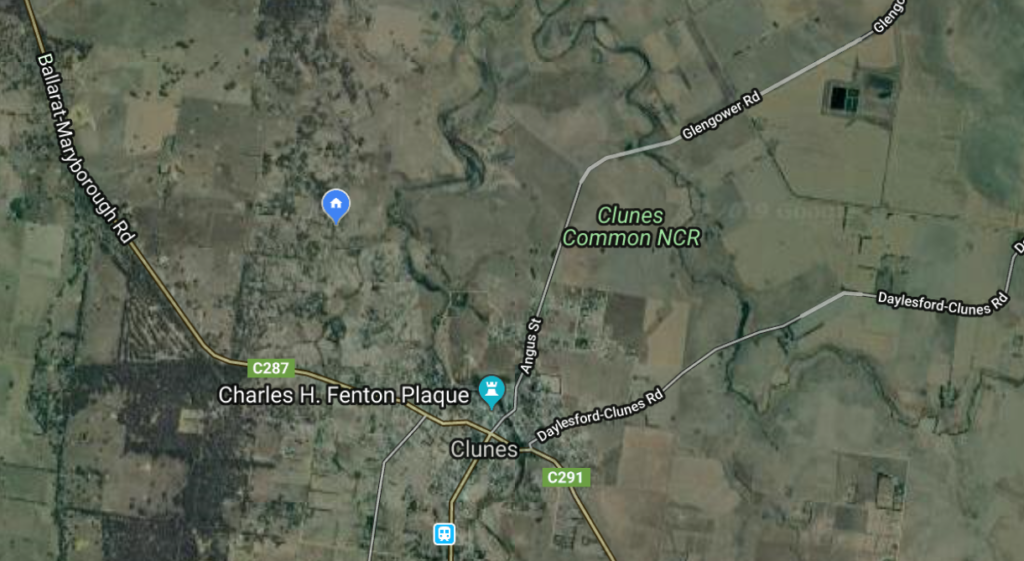

If you want to go and see it, the Clunes Town Common lies north of the present township, straddling Glengower Road. Bracketed by Birch Creek to the east and Creswick Creek to the west it covers about 216 hectares. Its boundaries remain as they were set when first proclaimed by the Victorian Parliament in 1861.

In those times, well before the advent of modern social welfare support, town commons were an essential part of the fabric of the surrounding community; as pointed out by researcher Ben Maddison in A Kind of Joy-Bell: Common Land, Wage Work and the Eight Hours Movement In Nineteenth Century NSW. “In 19th century New South Wales (and Victoria) the commons – denominated as either Temporary or Permanent…were set aside for travelling stock, pasturage, timber, water, indigenous communities, camping, recreation, ‘public purposes’ (schools, churches, cemeteries) and village, town and suburban expansion.”

In local terms this meant that “every inhabitant within the Municipal District of Clunes be entitled to departure six head of cattle or horses on the common”, and that a herdsman receiving a wage of 50 pounds per annum would be appointed to manage stock placed there. Later both Chinese and European residents could pay five shillings for a garden licence issued by the Department of Land and Survey (today’s DELWP) to “enter upon Crown Land not exceeding in area one acre for the purposes of garden and residence”.

However, unlike in the English tradition of productive common lands which had always been an insurance against hard times, common lands in the colonies were often little more than a resource to be exploited. The often became a locus of competition or conflicts over stocking rates and boundary maintenance and were frequently neglected with weeds, rabbits and mining activity contributing to their eventual decline.

The Clunes Common suffered from these issues and by 1918 the Ballarat Courier had a small news item titled: Clunes Common Recommended for Subdivision. But while the other town commons were carved up the Clunes Common remained largely intact and in regular use right up to 1960s. One of those people who remembers it well is John Overberg who settled in Clunes with his parents and five siblings from Holland in 1955.

“We had a house cow, as many people used to in those times, for milk and to make our own butter, cream and cottage cheese. The cow would stay at the house overnight but after milking in the morning you would just let it loose on the common and after school you would collect it and milk again. Sometimes you had to walk a couple of miles to find her. We also had about 16 goats there. The common was certainly an important asset to people like us to help make ends meet. It was also a great playground as we grew up.”

But by the turn of the 1970s the Clunes Common was little more than unused public land and was leased to a local farmer. It is now fully fenced and off-limits to the public. But few tears were shed at the time because society had moved on.

The old dependence on laborious activities such as maintaining a milking cow was hardly necessary when supermarkets could provide such produce cheaply and reliably. What’s more, with the emergence of the sort of social security net taken for granted today families no longer have to grow their own food or collect their own milk to survive, they can do it for fun.

There is also the fact regional councils no longer allow dairy cows to wander on the outskirts of towns nor permit mobs of goats to amble down suburban streets looking for blackberries to eat. The past is certainly another country.